How do hash tables work

In this post I will cover and expand a little bit on something from the CS101 Course of Udacity with David Evans. If you like this topic I definitively recommend you to check it out, it’s free.

Introduction

“The problem of measuring cost, analysing algorithms and designing algorithms that work well when the input size scales, is one of the most important and interesting problems in computer science.”

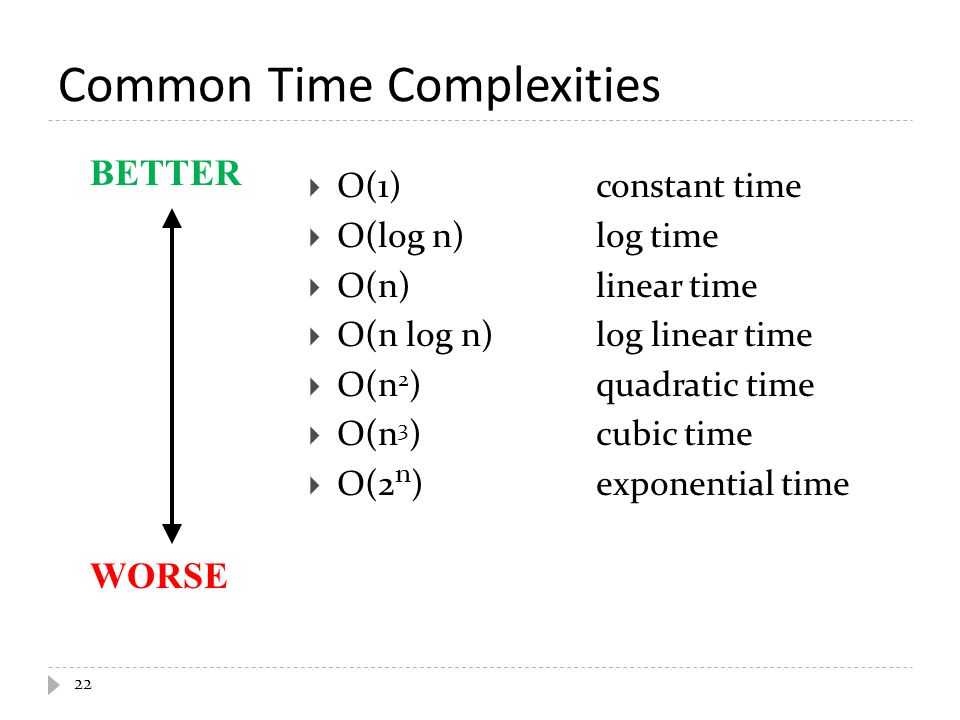

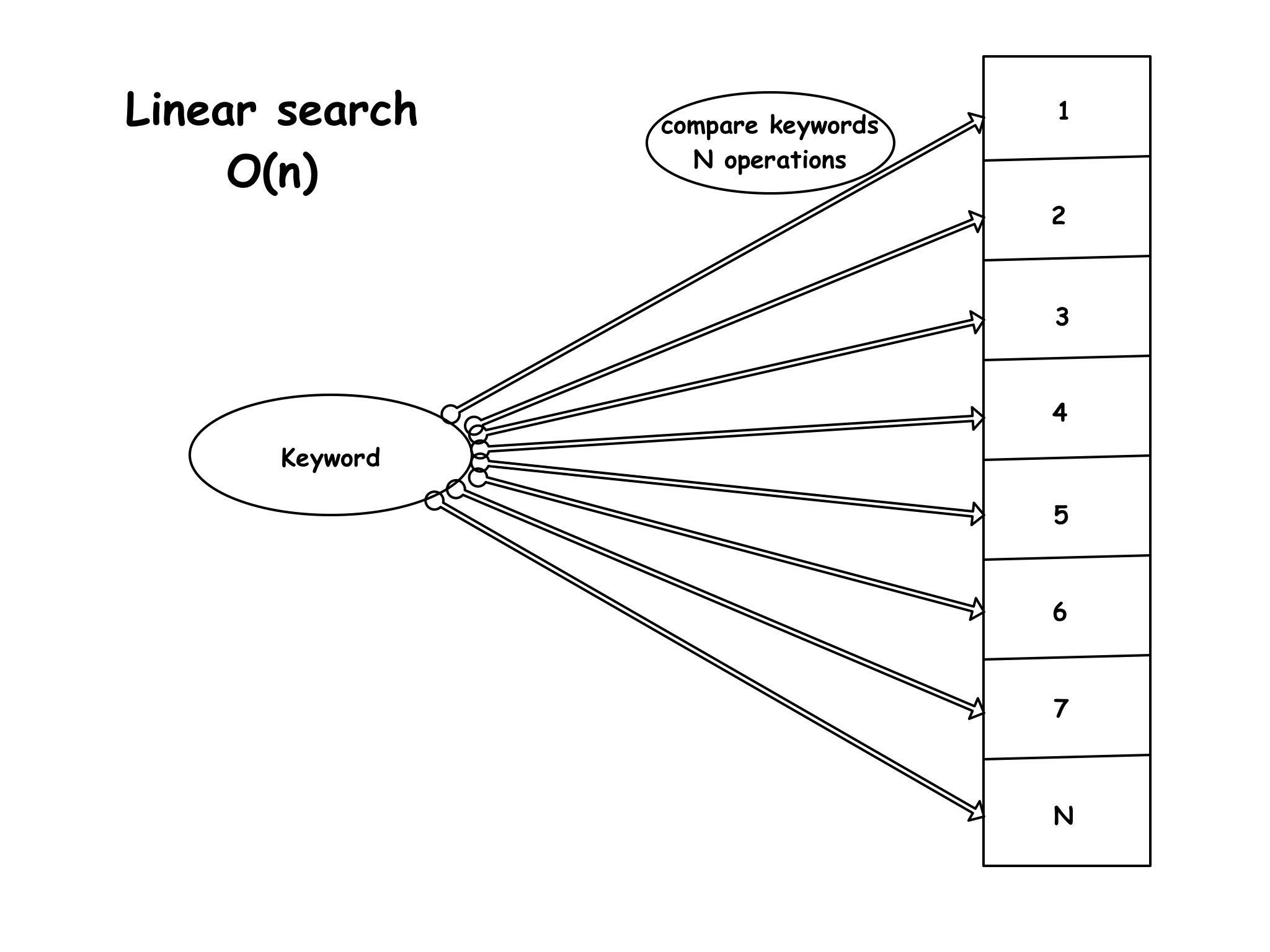

For example when looking up a value in an index of values, or key-value pairs. Normally the lookup time would increase linearly with the input size. If you have 10 values the algorithm would have to check them one by one, in the worst scenario all 10 values, before the right one is either found or the list is exhausted. If the size of values doubles (20 values), the lookup time would take twice as long in the worst case. But what if there is a better way to scale? There are different approaches, like search trees for instance. On average search trees have a time complexity of O(log n). This means that if the number of values is 16, the algorithm has to complete at least 4 ‘steps’ to find the position of the value –> log2(16) = 4.

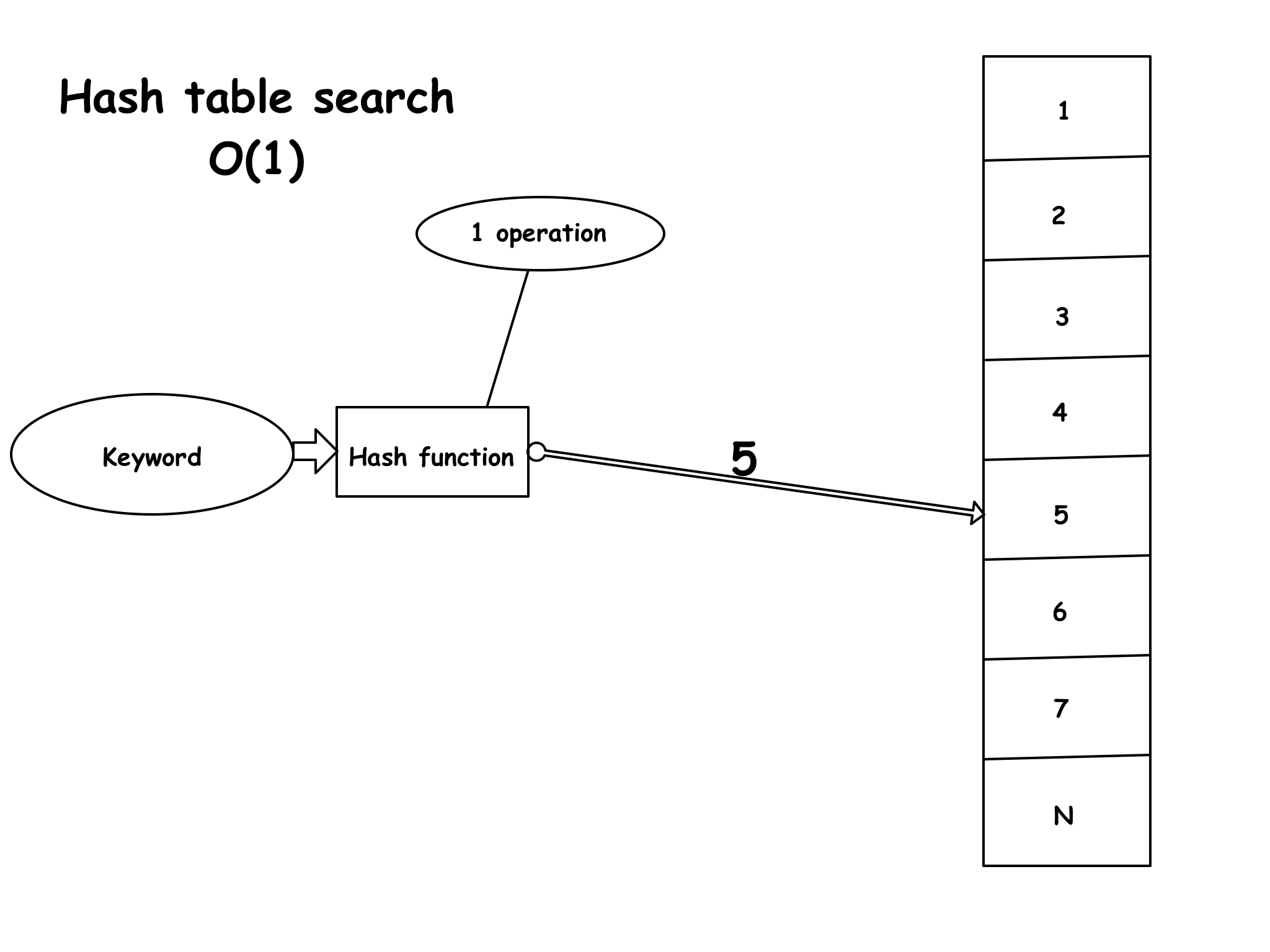

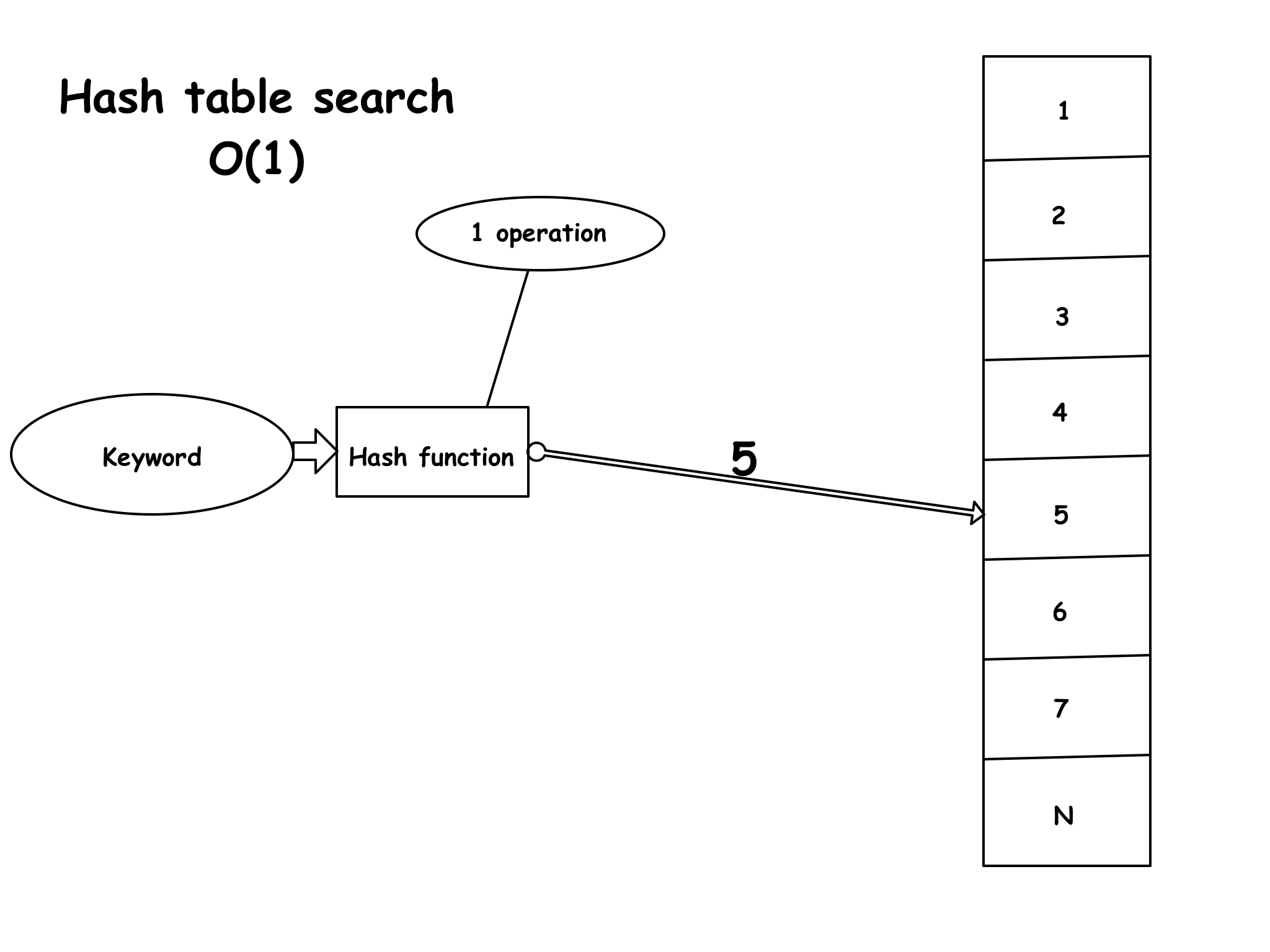

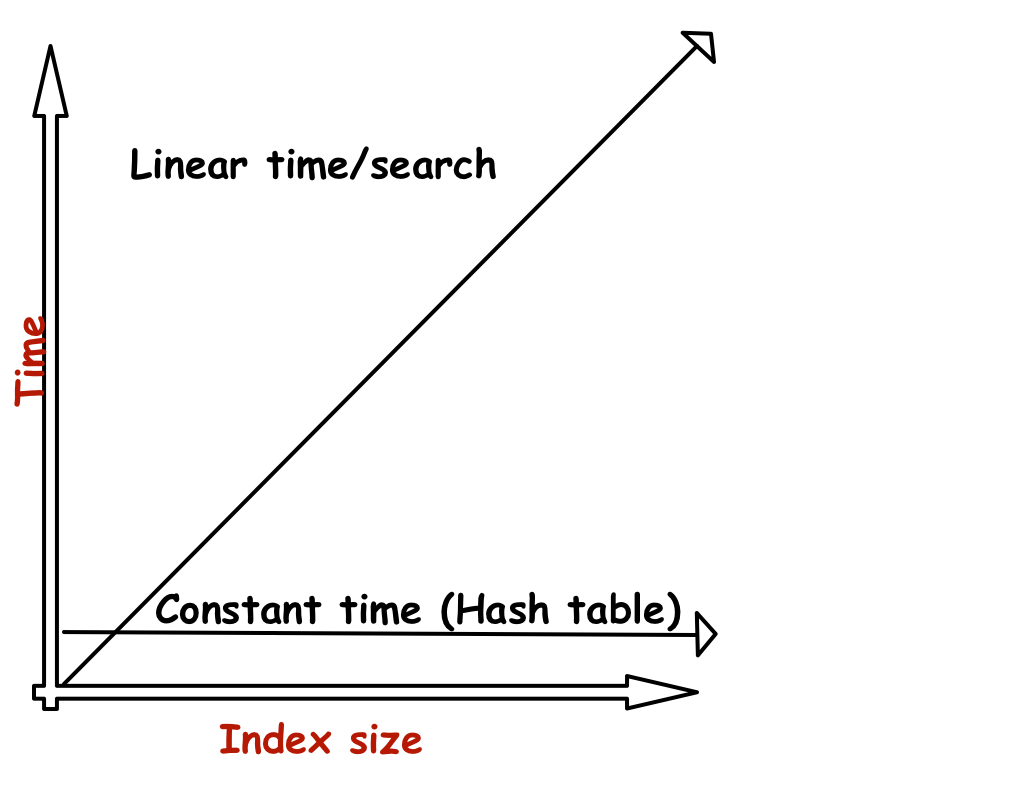

Of course the best thing would be to decouple the time (number of operations/seconds) completely from the input size. This is what hash tables enable to do. On average each lookup is independent from the number of elements stored in the table. Hash tables have a time complexity of O(1), meaning that they perform lookups in constant time, rather than linear time. This is very important as many types of software depend on constant time in order to operate efficiently, like search engines and database indexes.

So how exactly does a hash table work?

The basic concept behind hash tables is to do the computation just once on the keyword instead of the entire index. I’ll try to illustrate it graphically.

There are multiple ways to compute a hash, a simple way would be to base it on the first letter in each keyword, similar to an alphabetic index of a book. Each entry in the index of the table corresponds to a letter and contains all the keywords beginning with that letter. This isn’t the best method. The problem with this method is that it can only speed up the look up by a factor of 26, as there are 26 letters in the alphabet (26 buckets for our words). And this again would only be efficient if the buckets had the same size, which isn’t the case because there are more words starting with S and T than with X and Q for example. Thus the buckets would have very different sizes.

This can be fixed by solving two problems:

- The value must be a function of the whole word

- The words (values) must be distributed evenly between the buckets

In Python this data structure or type is called a dictionary. It provides the exact same functionality, so you could use it directly. But in order to better understand how a hash table works, let’s make one.

Our hash function, called hash_string, takes a string and the number of buckets b as input and outputs a number between 0 and b-1. You can use two Python operators to convert characters to numbers and viceversa. The ord (for ordinal) which converts a one letter string into a number, and chr (for character) which turns a number back into a one-letter string. This two operators are inverses which means that one function is the reverse of the other.

ord(<one-letter string>) → Number

chr(<Number>) → <one-letter string>

# try this in the python console

chr(ord('a')) --> 'a'What is needed next is a way to map the keywords to a range of 0 to b-1. For this you can use the modulus operator. The modulus operator (%) takes a number, divides it by the modulus and returns the remainder.

Example:

14%12 = 2In Python:

print(14 % 12)

2Now making use of the modulus operator, you want a way to calculate the hash string, using not just the first letter of the word like this:

def bad_hash_string (keyword, buckets):

return ord(keyword[0]) % buckets # output is the bucket based on the first letter of the keywordThe example above would result in a bad distribution of values in the buckets as you will see in a moment. To prevent this from happening you can just sum up every number coming from the ord() operator of every letter and then perform modulus of the sum like this:

def bad_hash_string (keyword, buckets):

def hash_string(keyword, buckets):

s = 0

for c in keyword:

s += ord(c)

return s % buckets # modulus performed hereLet’s test both hash functions with a sample text from the web. Check out the code download link for the complete code so you can try it for yourself. Firstly save the following text file to the folder your python code is located. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1661/pg1661.txt

f = open('pg1661', 'r').read()

words = f.split() # initialize all the words from the page 'Adventures of Sherlock Holmes'

counts = test_hash_function(bad_hash_string, words, 12) # obtain the counts for the bad hash string

print 'bad hash_string: ' + str(counts)

# [725, 1509, 1066, 1622, 1764, 834, 1457, 2065, 1398, 750, 1045, 935]

counts = test_hash_function(hash_string, words, 12) # find the distribution for the good hash function

print 'good hash_string: ' + str(counts)

# [1363, 1235, 1252, 1257, 1285, 1256, 1219, 1252, 1290, 1241, 1217, 1303]As you can see, in the second print the values are distributed much more evenly throughout the buckets than in the first one, where the distribution is a function of the first letter only.

Part 2: Benchmarking

Speed difference of a Hash table and a normal lookup Notice: This is by no means a perfect benchmark, it’s just meant to illustrate the speed improvement gained by using a simple hash table implementation.

For this test I will use the pythonbenchmark library, and a big index which I’ll generate with the make_big_index function. Jump to the bottom of the page for the complete code. The lookup function is the one which just goes sequentially through the entire index and compares every single key. This operation as we will see, grows proportionally with the index size. The second function called hashtable_lookup is our simple hash table function, which instead of running through the entire index, just jumps directly to the right bucket. This should happen in constant time, independently of the index size.

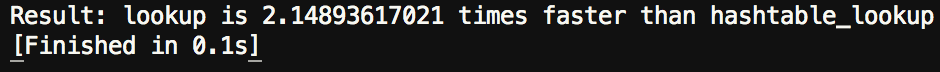

Let’s test the two functions with a tiny index of just 10 values. And run the test 10 times.

index10 = make_big_index(10)

# compare_function(function1, function2, number_of_tests, htable, lookup_key)

compare(lookup, hashtable_lookup, 10, index10, 'udacity')Output:

So far the lookup function is faster than the hash table lookup. This is probably due to the fact that the index size is so tiny, the cost of going through the 10 values is cheaper than calculating the hash of the keyword.

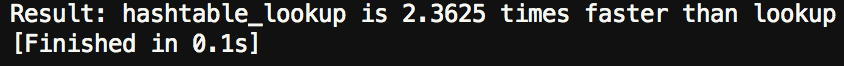

Lets test with an index of 100.

index100 = make_big_index(100)

# compare_function(function1, function2, number_of_tests, htable, lookup_key)

compare(lookup, hashtable_lookup, 10, index100, 'udacity')

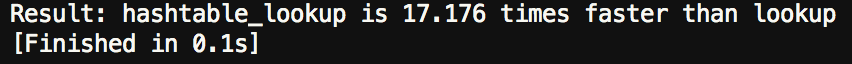

Index: 1000

index1000 = make_big_index(1000)

# compare_function(function1, function2, number_of_tests, htable, lookup_key)

compare(lookup, hashtable_lookup, 10, index1000, 'udacity')

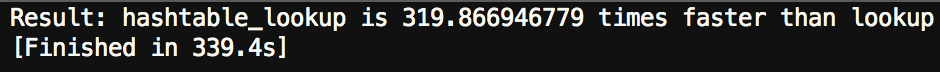

Index: 100000

index100000 = make_big_index(100000)

# compare_function(function1, function2, number_of_tests, htable, lookup_key)

compare(lookup, hashtable_lookup, 10, index100000, 'udacity')

Notice how much faster the hash table is with an index of just 100.000

This is because as the size of the index grows, the time difference between a normal lookup and a hash table grows linearily with the input size as shown in this graphic.

Now imagine what would happen with an index of billions of entries like a search engine. Without some kind of hash table something bad would happen, you can do the math :)

For the sake of keeping this Blogpost short, I won’t dive into the complete code but you can download it and try it out for yourself. It’s pretty basic and by no means the best implementation of a hash table, but I think it will help to understand how a hash table works and the underlying concept. There are also downsides to hash tables, like collisions. This implementation uses separate chaining to resolve collisions.

Hope this helps

Karl

Comments